Computers can’t see evolution. The changes that humans understand so well – decay, emergence – make computers blind. This means machines can’t assist medicine when a disorder fundamentally changes as it progresses. Like a cellular response to a virus that cascades until it attacks the body it was protecting. Or the way a physical shock can disrupt sleep, years later. What might be possible if computer systems could predict how situations will change as they carry forward? If machines had these eyes.

Studies suggest that humans naturally reason about transformation using form and dynamic imagery (Leyton, Nersessian, Talmy). Charles Sanders Peirce, foundational theorist for computational logic, described comprehension as “moving pictures of thought” (Peirce, Pietarinen). Over the next 18 months, myself and six collaborators will take a first step towards supporting machine reasoning using evolving structure, rather than probabilistic or statistical methods. This research is titled Design in Information Flow but for ease I’ll refer to it as the form project. The results will support a new tool for small biomedical teams, enabling them to visualize separate pools of data as merging flows. Our approach is novel in that it draws from artistic knowledge: when our system decides how information should fit together, it will refer to elegant streams of motion.

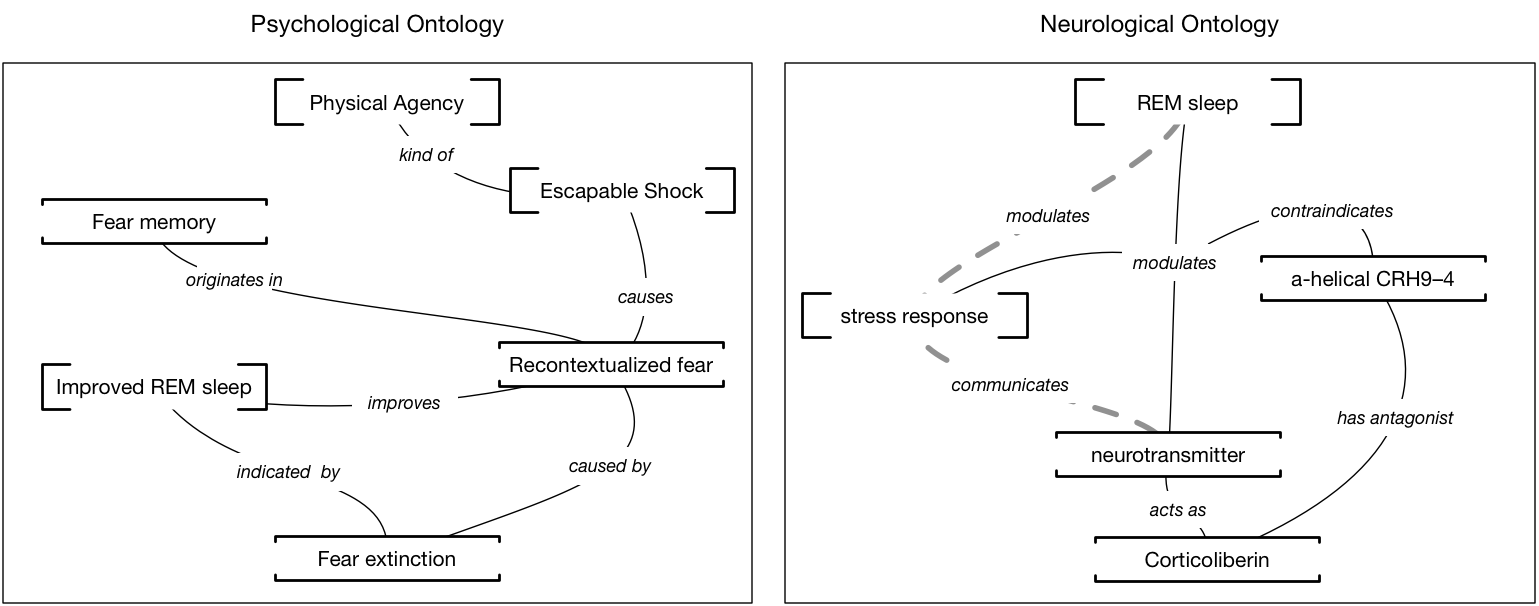

At present, machines arrange information using something like the above diagrams: ontologies. Here are two different ontological networks, each mapping different but related bodily systems: psychological and neurological. A traditional reasoning system uses this sort of reference framework like a dictionary, in order to understand how information fits together. However, with every medical discipline, or new purpose, the framework is likely to be different. Some say the most useful aspects are found in those specific details.

The problem is, a computer system can only use one reference framework at a time — one dictionary. So when an illness progresses through numerous fields, computers can’t follow. Consider the above diagrams as two states that need to be connected, because the disease either progresses between them, or combines them. Computers struggle to join such reference frameworks automatically (a human has to do it manually). This problem has led to long-standing efforts to enable the automatic bridging of ontologies. Relatedly, large programs such as the OBO Foundry are devoted to the standardization of terms across different fields in medicine.

The problem isn’t the networks themselves. It’s that there’s no easy way to transition between them, because they’re structured in a bottom-up manner. Rails of computational logic join, sleeper after sleeper, until the whole is the sum of its parts. But that’s all. Without an overall characterization of the whole, there’s no way to know how it can evolve into a slightly different whole. As a result, when computer systems are given information about different aspects of a body, they produce data silos instead of integration.

The arts handle knowledge differently. Artistic forms harness a top-down perspective, where sweeping characterizations of processes such as trauma or growth are possible. One of the contextual devices that enables this is analogy, which has been argued to be a powerful form of reasoning when modeling dynamic situations (Nersessian). We’ll investigate this and other artistic devices during this project: repetition, focus, perspective. The way deviance swells into new order.

These principles will emerge from overlapping research: my own, and that of Niccolo Casas, architect and designer. My narrative analysis has mapped how story mechanisms can integrate information from numerous contexts, and in the process, generate an additional, meta-layer, which coheres them. Insights from the Japanese science of katachi (a science of form) suggests that in this meta-layer, the expression of information reflects the rules of its own construction: aesthetic design.

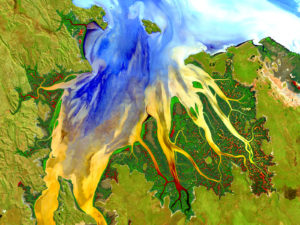

Casas investigates pattern configurations that arise through natural processes, such as catabiosis and entropy. His PhD explores how flow favors the optimal course, the path that conserves energy, in both nature and design. This form project will borrow Casas’s eyes and intuitions about the transitional paths between diverse conceptual networks. Animations of evolving structures will be produced with the assistance of Alessio Erioli, Engineer and Senior Researcher at the Università di Bologna.

Our biomedical examples and data will be supplied by researchers Patric Lundberg, Larry Sanford and Richard Ciavarra, at the Eastern Virginia Medical School. The examples will concern studies from the impact of viruses on the immune system and microbiome, and research into recovery from traumatic shock. Ted Goranson, who was a senior computer scientist with DARPA, will create hooks between the visual model and the computational back-end.

This work is made possible by a grant from the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative, as part of its series of advanced interdisciplinary projects in which art, medicine and engineering intersect. It will build the foundations for a tool that allows small medical teams to see shifts and anomalies in data, and pinpoint the most valuable way to allocate resources in future experiments. This new visualization method will occupy territory somewhere between informatics, medicine and art.

Computers are not moved by a beautiful line. As my eye travels along that lovely curve, the shape unfolds and I do with it. It is compelling. Elegant motion displays a special logic. It finds the optimal path more easily than I can. It seems effortless. That beauty: it knows something about how to arrange information.

#beautifulscience

@keckfutures

Beth this is a fascinating piece you wrote! I look forward to reading more. It has also given me food for thought within my own work and potential research avenues I had not previously considered.

I’m looking forward to talking with you about your research next time I’m in Melbourne!