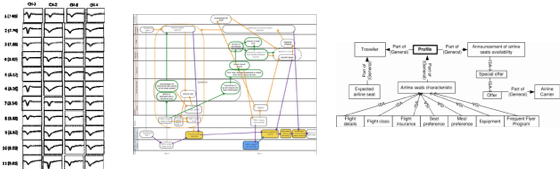

My team are halfway through developing an approach to computational reasoning that represents interactions between whole systems, such as neural circuits and cognition. I’ve led other interdisciplinary projects but never with such dramatically different disciplinary members: neuroscience, narrative analysis, computer science, biology and design. As a visual example, consider the different modes of modeling we each use, below. One of our goals is to bring the strengths of these methods together:

Neuroscience narrative analysis Knowledge representation (computer sci)

Biology (gene activations) Design

So as well as addressing our funded problem, we’ve also been working on the meta-issue of how to integrate our ideas. Without this, we can’t even discuss the project, let alone innovate.

This requires the construction of a new space, one we all own. I’ve started to refer to this space as a shared story. I’m thinking of something particular with this phrase. I make animated models of how inferences are woven together in an unfolding story. In this example from Red Riding Hood as a Dictator Would Tell It, the process of integration is gradual, until select elements from fairytale and dictator contexts are connected in a new frame of reference (the one produced by the story). Narrative machinery does exactly this – it reframes and reassembles information so that unexpected combinations of ideas can be linked and comprehended. Storytelling builds a new context.

This same process is needed in collaboration, especially when the disciplinary spread is extreme. For example, in our group, the word system means something different to everyone. For our biologist, it’s a bodily process. In computer science it’s an implementation. In narrative analysis it refers to a regular way of doing things. We didn’t need to build a completely new vocabulary. But we did need to figure out what terms were going to be important in this project and define core notions, like system, in a way that accommodated our combined needs. We needed some sort of common frame of reference, one that could be accessed by all participants. Otherwise, passing ideas between fields would be tokenistic. Or worse.

Department of Energy dumping toxic waste at Hanford, Oregon.

When a group doesn’t succeed in coming together, the results can be catastrophic. William Lawless, now a research fellow at the Navy Research Lab, tells a true story about how a thousand people with doctorates made a very stupid collective decision on behalf of the Department of Energy: they decided to bury nuclear waste in cardboard boxes in the ground (Lawless, 1985) (Ledford, 1984) (Mayell, 2002).

Anyone who has been part of an ineffective committee might understand how this is possible. Without good leadership, a group is capable of making dumber decisions than any one person could usually manage. This poor decision-making reflects a compromised process: instead of being guided by a shared story, the project is instead driven by factors that are non-intrinsic to its goals, such as peer or societal status (Cohen and Lotan, 2014, p. 36). Decisions become informed by a struggle for dominance. One way to think about collaboration – especially interdisciplinary collaboration – is that a shared story enables issues related to the target problem to dominate, rather than the personality politics of the group itself.

I’m currently writing a chapter about the relationship between collaborative frameworks and narrative processes, for a book titled Computational context: Why it’s important, what it means, and can it be computed?, supported by the Navy Research Lab. It discusses interdisciplinary collaboration in general but also how my team built a common perspective.

Our approach: we wrote three peer-reviewed papers to act as stepping stones that gradually integrated our work. In the first paper, I recast my previous work towards the new project. In the second paper, I linked my research to the collaborator whose ideas were closest to my own – this was Larry Sanford, neuroscientist at the Eastern Virginia Medical School. We found a common feature across our two fields – the reorganization of memory structures. In a third paper, everyone came together for a special issue of Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. Here, we finally found a common structure across all five disciplines and clarified the terms we’d use. That common structure was actually a process that moved through several stages: emergence, abstraction and self-reference.

There are surely many ways to incrementally integrate a group, not just by writing successive papers. This worked for me as a writer, because it was a larger version of the process of weaving fragments of information in fictional stories. In both cases, the process felt like free-fall. I don’t know where this is going yet. I’ll just keep joining any pieces that float past. Like writing, this required faith that my intuition would guide this process somewhere.

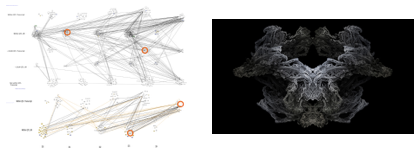

The scariest step was making the below model, in which information from Patric Lundberg’s herpes research was presented using the operations of my narrative modeling technique.

(If this is too small to read, try making the browser window larger)

I had previously used this graphical method to track narrative inference in literature, film and TV shows such as Game of Thrones. But I had the strangest hesitation about using it to draw biology in this way. It was as though choosing a wrong connection would undermine the entire project. As though attempting it might result in proof that it couldn’t be done. It was worse than facing a blank page as a writer, which I have tricks to work around.

I sat with computer scientist, Ted Goranson, and Patric’s work, and we painstakingly built the new description over three days. Each step felt precarious. Why? Perhaps it was simply because there were no rules or firm ground. We stepped into empty air, with no accompanying theory or literature. Only the rope of our ideas connected us to the rest of the world.

The result is the first representation of system-level biological and neurological behavior using operations of context, as usually observed in narrative. Our task of creating this, or the shared story that makes it possible, isn’t finished. We are building it as we go, and that group coherence probably won’t be firm until the project is finished.

To better support this collaborative process, I’m collecting qualities from the arts that enable the development of a shared story. My favorite so far is a tolerance for ambiguity – as described by Cindy Foley at the Columbus Museum of Art. A sense of ambiguity, of spaces becoming less tangible and more dynamic, comes with moving beyond your discipline. The feeling can be disorientating and I’ve seen promising projects implode from the fear it inspires. Everyone races back to comfortable scripts – their discipline or social status. No-one wants to wheel through empty space.

In the next stage of this work, my team will define where the innovation is going to be in this project. Every field takes its own scope of innovation for granted. In creative writing, the novelty comes from casting a new perspective over reality and ironsmithing language to hold it; in neurobiology, it come from making a new theory that can be traced in brain or body tissues; in design, the novelty comes in an act of abstraction that also reveals paths of formation. In this project, the innovation is in creating a method that can capture and communicate unexpected concepts – ideas not already already in it’s reference framework. These especially pertain to qualities that emerge across systems, for example, characterizing the health of interactions.

This project brings together numerous modeling approaches to better represent these system-level interactions. A key device that supports this is analogy. In collaboration, each of us describes an example, such as the disordered learning that occurs in PTSD, from our different perspectives. The example thus becomes a rosetta stone, an underpinning abstraction that connects the different perspectives together, even if their vocabularies cannot be reconciled. It can be jarring to hear something familiar in a foreign format. I remind myself to have patience and be willing to temporarily know little. Through this process, I’m starting to see where our innovation is, and how to build it.

When writing a story, you discover its rhythm as you work with the actual text, making new associations. Each new idea feels tentative but you still jump to it, in order to shift the horizon line. Trust is needed that when you step into empty air, new ground will form beneath your foot. In both interdisciplinary collaboration and storytelling, taking the step invents the physics.

References:

Cohen, E., and Lotan, R., 2014. Designing Groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogeneous Classroom. Teacher’s College Press, New York.

Lawless, W., 1985, Problems of Nuclear Waste, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, 41, 10, p. 38-42.

Ledford, J., 1984. Engineer claims DOE has problems with radioactive waste. United Press Int.

Mayell, H., 2002. Idaho, U.S. Battle Over Nuclear Waste Dump. National Geographic News, April 2, 2002, accessed online November 10 2017, https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/04/0402_0402_nuclearwaste.html