The Virginia Modeling and Simulation Center (VMASC) is prototyping a narrative modeling tool that expands on my original design – a platform that annotates how interpretation changes over time, in the real world. This modeling platform is planned to include the lyrical flow dynamics of Niccolo Casas, a follow-on from our collaborative project supported by the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative, and enable us to produce examples from researchers at the Eastern Virginia Medical School.

(The final report for that project is here).

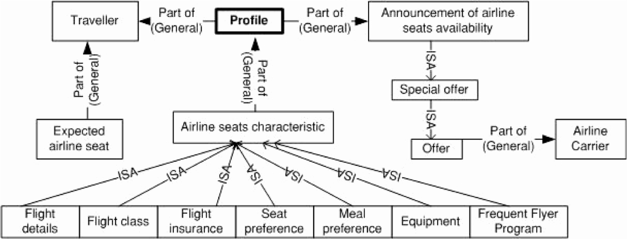

This modeling method records evolving interpretation, and as such, was developed using Keynote (the Apple version of Powerpoint). When humans reason in the real world, we draw from multiple frames of reference and are constantly adjusting the relationships among them. I used Keynote to animate the way reference frameworks change; they usually do not move. They look something like this.

Ours are more complex, like this:

And they evolve, like this:

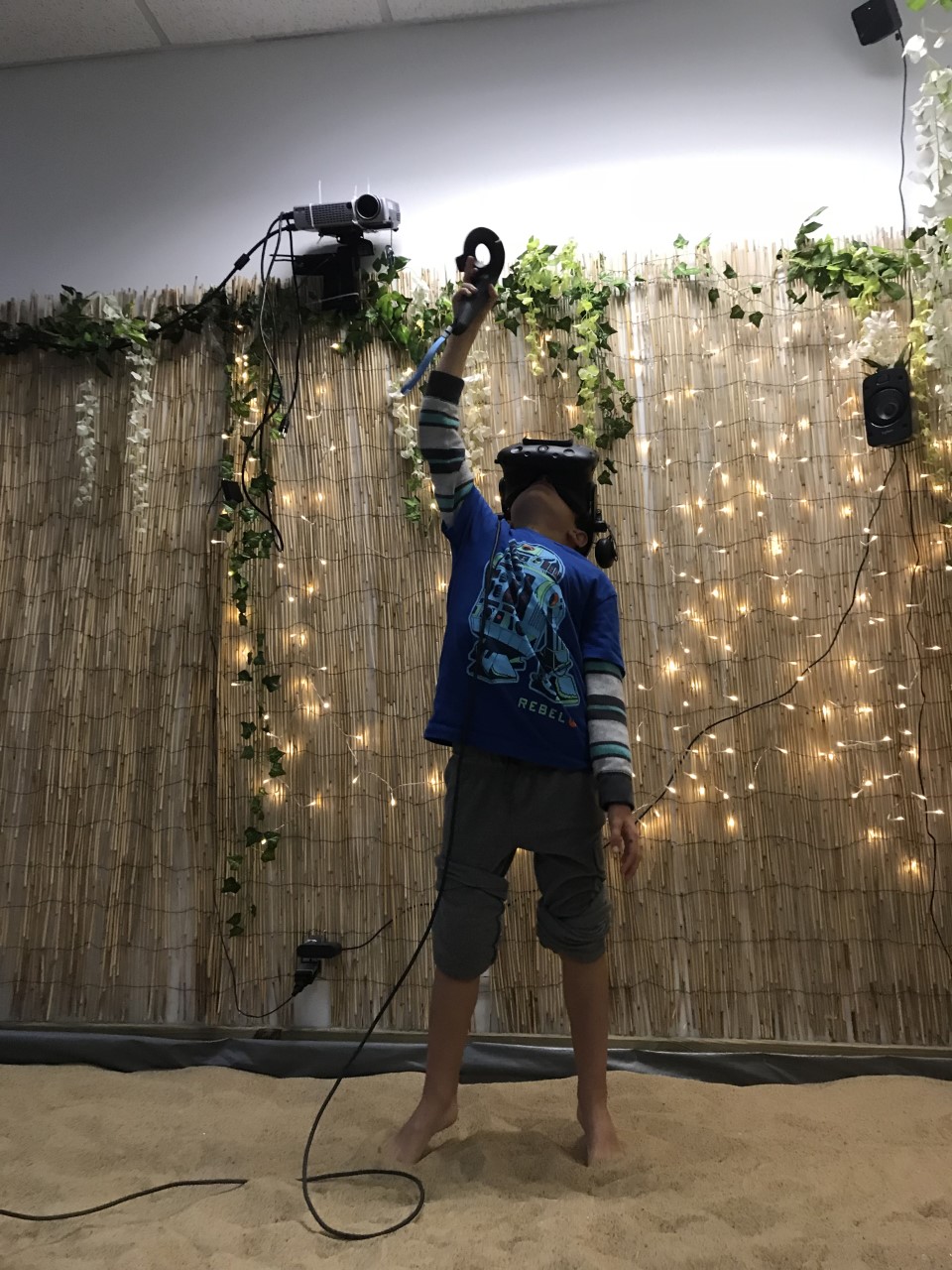

Now the method is moving to a new level. We’ve shifted from Keynote (which animates a white sheet of paper) to Unity (a physically inhabited 3D gaming environment where you can control time and physics). This changes everything.

I spent yesterday inside this virtual space while the VMASC guys, John Shull and Alex Nielsen, experimented with the physics. I usually spend all day with nodes at my fingertips. My alphabet is nodes – nodes with text printed on them, to represent concepts that can be strung into networks, to show how knowledge is built. I show how story interpretation works by making node-networks that evolve, demonstrating how our ideas connect and move during real-world comprehension. But it has never been like this before.

I put on the helmet. Now I’m walking on a field with the sun high above and an infinite horizon all around. Nodes appear in the calm air. Nodes are bubbles, popping into existence, and then more nodes appear as mushrooms across the field. My thoughts are written on them, as usual.

With a keystroke, John changes their orientation. When I walk away, the orbs follow me like puppies, bumping my heels or sneaking under my elbows. Another tappy-tap-tap and gravity disappears. The node in my hand floats up, away from me, into the deep sky. There go my thoughts. All the others are released too, rising like balloons from a football oval. I look skyward to see my mental map rise, and the balloons travel so far above they become a constellation, dots of ideas spreading into space. Long after I can’t see them any more and take off the helmet, I notice they are still on the map on John’s screen, being tracked somehow in its grids. He shows me how he can retrieve them and put them back on the field, like wild animals tagged by GPS. They are never lost.

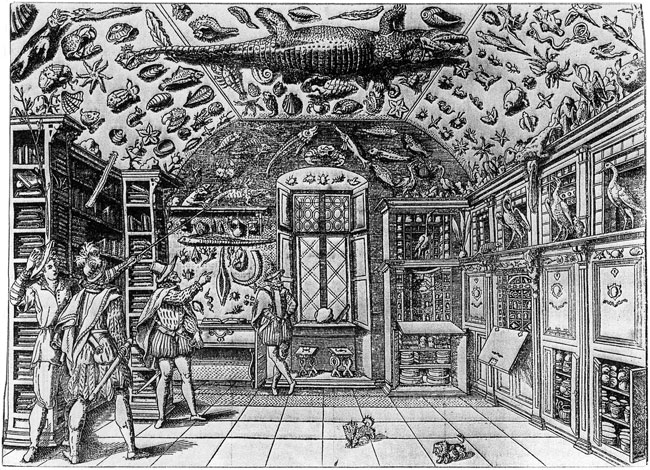

When I first met Ted, he told me about Francis Yates’ The Art of Memory, which explains how mnemonic devices developed throughout history. In particular he described how Shakespearean actors could remember their lines by memorizing concepts in relation to objects positioned around the theater. My modeling method has always worked with this kind of projection, mapping thought onto structure and watching it change. It’s one of the reasons I’ve been so involved with the Symmetry and Katachi communities over the past 15 years (these groups will converge in a conference in Japan in November 2019). One of the first presenters I saw from this group was Tohru Ogawa, who said that when you map one structure onto another, the path of the first gives clues to new possible innovations for the second.

Another connection to this work is the Wunderkammer (curiosity closet), a historical precursor to the museum, brought to this project by Alex. The wunderkammer was a large space in which the objects collected from foreign countries were brought together for analysis. Positioning newly discovered objects in a room helps to classify them. The taxonomy is based on morphology and function.

In a sense, narrative is a kind of classification system like this, except that it allows you to flexibly reorganize your existing collection based on each new instance you acquire. Rather than being flummoxed by this re-organization, narrative devices anticipate it.

In this project, we lay ideas on structure and then watch how re-assembly changes them. The new affordances of Unity 3D add so much power to this process that it changes my conceptualization of the method itself.

For example, we will probably leverage solutions from film-making, to model cognition. When I currently show reinterpretation (such as when a murderer is revealed in detective fiction), I draw a 2D line on a page that reaches back into a past structure, brings forward all the previous associations with that character, newly contextualizes them, and then builds new networks on top of it. Grids fold across the page, in and out of sight. In practicality, Keynote groans like old knees and gives up before I can get to the good parts.

Now those node networks will throttle past like a steel freight train. With Unity, we can simply place cameras at different points along its path, to capture what is happening at multiple places simultaneously. When I want to show reinterpretation, a funnel will emerge from the front ‘engine’ and reach back into space towards the caboose, like reaching from my front driveway to a spot near my kid’s school. A new camera angle will appear to show the close-up as the funnel lands, finds the needed structure and then carries it back to where the viewer stands. The second camera angle folds away again when finished.

Filmic devices like these will help us deal with some of the time and scope-based problems we’ve struggled with in Keynote, like representing action at two different places at the same time (hence multiple cameras).

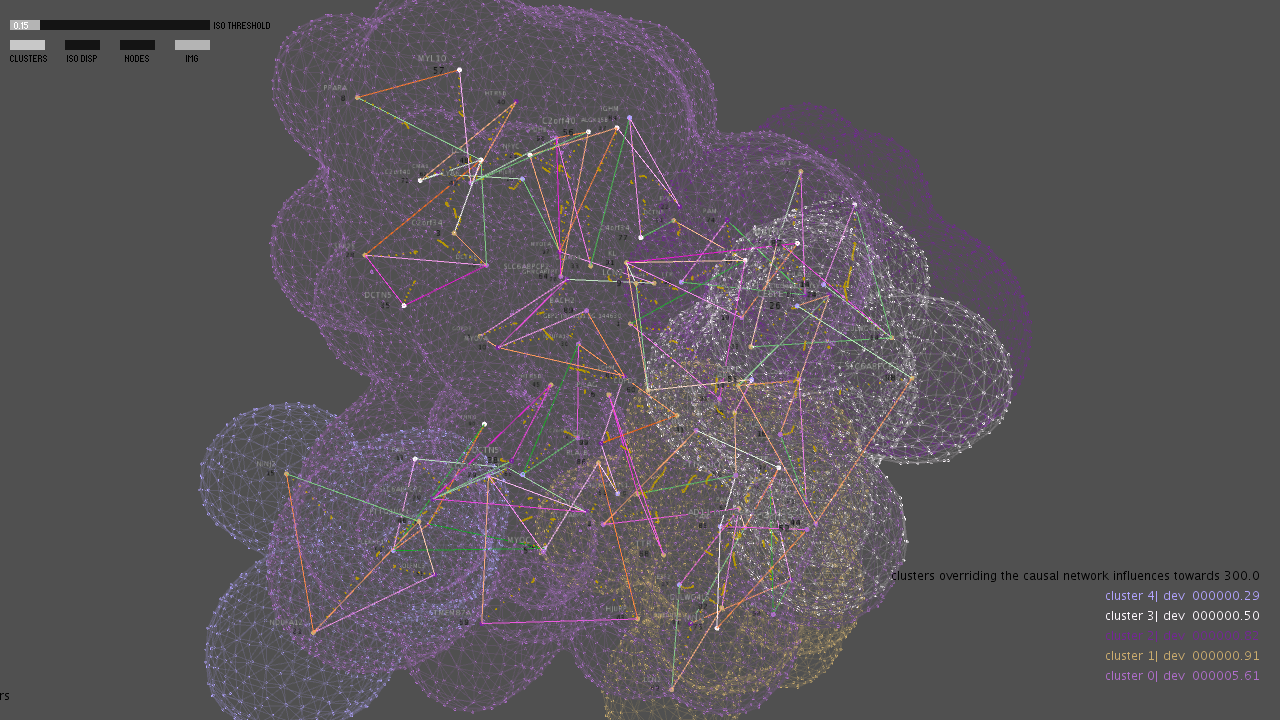

This will also help bring in the full gravity of Niccolo’s approach to flow dynamics, when we are able to render streams of information like this:

(from the Unity visual effect showcase)

Here’s another new solution – in virtual space, we don’t need a keyboard to write text on new nodes. Instead John and Alex made a tape recorder, so we speak the needed words aloud and they’ll be recorded directly – thus:

Finally, it’s easy to scale the user up and down in size. I tried it in a simulation of climbing Mt Everest. I could see how I would stand over my thought-networks like Godzilla, smashing or watching viral and neural signals converge. We’ll model through scale this way, from DNA activation to the innate immune response, and finally up to the narratives that stress or calm us. Oceanic tides of neurobiology.